- Home

- Foreword

- Contents

- 1. Retrospective and perspectives

- 2. At the heart of safety: high standards and leadership

- 3. Industrial safety and radiological protection: it’s behaviours that count

- 4. Pragmatism for the EPR2

- 5. The fleet upgrade: a colossal programme

- 6. Reactors that adapt to climate change

- 7. Nuclear fuel and reactivity control: the heart of nuclear safety

- 8. Competences: are we sufficiently demanding?

- 9. Changes in the electricity system: anticipate rather than suffer

- Appendices

- Contact

Navigation

Navigation

INTRODUCTION

New international impetus and renewed interest in controllable, low-carbon energies marks the end of the “nuclear hibernation”. Without the atom’s contribution, it will be difficult to do without fossil fuels and to limit global warming.

In a Europe reinvigorated by a new alliance, but held back by Energiewende, France and the UK aim to develop a balanced energy mix promoted by the EDF Group.

The reforms intend to improve the performance of our nuclear generation systems and must maintain safety. The simplification expected by all will require everyone to be demanding and rigorous in their behaviours.

NUCLEAR, ENERGY OF THE FUTURE: A TROUBLED HISTORY

There is an abundance of news on the international, European and domestic scenes. It confirms the return to favour of a particularly low- carbon form of energy in the energy policies of both industrialised and developing countries.

This repetition of history, this U-turn in the new context of the fight against global warming, is reminiscent of the ‘Atoms for Peace’ speech by US President Eisenhower at the United Nations 70 years ago. Promoting de-escalation of nuclear weapons in a bi-polar world, he proposed the creation of an international agency for atomic energy (which became the IAEA four years later) to develop civil nuclear energy for peaceful purposes.

Faced with climate change (see Chapter 6), the energy crisis, and the need for energy to drive economic development, countries will have to find a controllable, low-carbon energy mix. In this context, nuclear energy combined with renewables is a solution, and seen as the only solution for large organisations like the International Energy Agency (IEA), IAEA or the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). According to the IEA report ‘A New Dawn for Nuclear’, “nuclear energy plays an important role in the global path towards zero carbon; it will double its capacities in 2050 under Net-Zero Emissions”. During COP28, 22 countries representing over 40% of the world’s GDP signed up to a commitment to triple nuclear energy production by 2050 and assure access to energy for all. China, India and Russia were not among the signatories. For the first time, the final declaration of COP28 mentions nuclear energy and calls for a ‘transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just and equitable manner, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science’, despite pressure from the 13 OPEC member countries fearing that the proposals “put our people’s prosperity and future at risk”.

Focused more on its development than decarbonisation, China continues to roll out its nuclear programme at a rapid pace: 54 reactors are already generating 57 GWe, with 26 more reactors being built to produce an extra 29 GWe. On the verge of becoming the world’s leading nuclear operator, it has access to vast swathes of empty land to develop solar, wind or hydroelectric projects. Some of these imposing facilities are built on the border with its Indian rival, which can be a source of tension.

Protecting nuclear safety from diplomatic tension and economic rivalry

At the end of the second world war, nuclear power was declared the energy of the future. The IAEA has a six-tiered mission statement, including that of establishing nuclear safety standards. After the Chernobyl accident in 1986, nuclear operators across the globe realised how important it was to work together to improve nuclear safety and founded the World Association of Nuclear Operators (WANO).

Who could have imagined, thirty years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, that a conflict on the edge of Europe could, in addition to the spectre of nuclear weapons, use nuclear safety as a method of rivalry? In 2022, the Zaporizhzhia plant was the first to be used as nuclear blackmail, with shelling capable of damaging its containment and independent electrical supplies. In 2023, its heat sink was threatened following the destruction of the Kakhovka dam on the Dnieper River. In the event of a total loss of river flow, cooling of the low-level decay heat from the six units, shut down for several months, could be assured by the back-up and emergency cooling reservoirs. Inspectors from the IAEA were able to carry out an independent check to make sure “there was no immediate risk to nuclear safety”. Regardless of the perpetrators, the international community must reflect on the principles of inviolability of nuclear safety in the event of conflict, based on the ‘seven pillars’ considered essential by the IAEA.

It is essential to make sure that the international agreements and partnerships signed during the cold war to protect nuclear safety can withstand political and diplomatic developments, as well as US export control regulations. The new major competitor, China, is promoting nuclear power as part of its investments overseas via its new silk roads, with construction projects underway in Saudi Arabia and even Turkey. After the country re-opened its borders earlier this year, it quickly took charge and has organised numerous forums supported by the IAEA (small modular reactors, (SMR), spent fuel reprocessing, etc.).

This is why all nuclear operators must maintain close relations and open exchanges between themselves. Marginalising or ostracising certain members puts nuclear safety at risk and thus the entire international community.

Nuclear energy now has the support of a large number of countries who must develop their own doctrines based on the overriding priority of nuclear safety in line with international standards and under the authority of independent organisations. The French model can serve as a legitimate reference, unless it is made excessively complex at a time when other major operators have started simplifying their own systems.

Euratom: achievements fall short of ambitions

To continue this nuclear retrospective, European countries were concerned with how to secure their energy supply during the post- war economic boom. In the fifties, the European community (Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands) launched two projects: the CECA for the coal and steel industry, and the EAEC (Euratom). It believes that “nuclear energy represents an essential resource for the development and invigoration of industry and will permit the advancement of the cause of peace”.

We obviously have a rather short or selective memory. Despite the Suez Crisis in 1956 and two successive oil crises (1973 with the Yom Kippur war, and the Iranian revolution in 1979), ideologies seem to be more powerful than facts. The irrational debate surrounding the phasing out of nuclear power is leading us to replace the hegemony of ‘black gold’ with either exploiting the other two fossil fuels, coal and natural gas (between them, these three provide around 80% of the world’s energy), or the mirage of new renewable energies, which, in the absence of storage solutions, are unable to meet growing energy needs on their own.

Though still in force, the objectives of the Euratom treaty have been defeated by the reticence of some founding states, with inadequate implementation means and institutional blockades. The main adversary of nuclear power in Europe remains a visionary Germany, who has preferred, for ideological and economic reasons, to become totally dependent on cheap Russian gas; it now finds itself forced to open up lignite mines to remedy their intermittent wind and fleeting solar power sources despite their massive investments. The Germans are faced with three sobering truths: a gloomy economic forecast, the status of a net importer of electricity (a third provided by nuclear energy, much of it from France), and the largest CO2 emitter in the European Union (rising by 8% in 2022).

A new alliance, relaunch of Euratom

France does not have any more oil or gas than it did in 1974, but it still has ideas! This is why it has taken the initiative of the Nuclear Alliance. In May 2023, fourteen countries in favour of nuclear energy met in Paris (Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, Finland, France, Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Sweden and the Czech Republic), with Italy as an observer and the UK as a guest. This united front promotes the revival of the nuclear industry in Europe. The Nuclear Alliance calls for the application of technology-neutral policies and the integration of nuclear energy into low-carbon energy funding mechanisms, whereas several countries, including Germany, Austria and Luxembourg, are seeking ways to exclude it.

Whilst nuclear safety has no price, it does come at a cost. The pooling of resources in Europe would make economies of scale possible in a sector that calls for significant investments. The Nuclear Alliance has estimated that nuclear energy could supply up to 150 GWe by 2050, provided that its current plants remain in service and that 30 to 45 large new reactors are built in addition to SMRs, the deployment of which has received the support of the European Commission. The industry expects to create 300,000 direct and indirect jobs, including 200,000 qualified positions, and 450,000 new recruitments.

Our Belgian neighbour has revised its energy policy, extending the service life of two reactors for another ten years although they were initially planned for shutdown in 2025. Reactors are being built or designed in nine Member States: in Finland (Olkiluoto 3 has been in commercial operation since April 2023), France (extension of the existing fleet, and a programme of 6 to 14 new EPR2s), the Czech Republic and Slovenia (French proposals to build EPR 1200s), Poland (6 or more reactors), the Netherlands (2 reactors), Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Lithuania, and Romania. Sweden has abandoned its 100% renewable objective for a 100% low-carbon solution. In the UK, Great British Nuclear (GBN) is an ambitious nuclear programme that plans to create 24 GWe of nuclear generation by 2050. The British government decided in late 2022 to become a 50% shareholder of the EPR project at Sizewell C, a key step in moving towards the final investment decision (see Chapter 4).

EDF’s CEO, Luc Rémont, suggested building on this EPR community (European Pressurised Reactor) evoking the importance of the word ‘European’ in its name: “As the only vendor and constructor of third- generation nuclear technology in Europe, […] the long-term strategic and industrial European partnership we propose will set a precedent for our continent and can become the pivot of a more resilient and independent European nuclear industry”. Yet competition with the US and their acolytes will be tough.

REBUILDING THE NUCLEAR INDUSTRY AS A MAJOR FORCE IN THE FRENCH ECONOMY

Actions after the Belfort announcement

After the invigorating speech given by the French President in Belfort in February 2022, the French energy and climate strategy confirms and details its main energy choices. In many respects, 2023 will remain the year during which we built a toolbox that will have to prove its effectiveness over time.

To quote Edgar Morin, “disorder is normal in complex systems, but it holds the source of a new order”. After years of stagnation, France is now faced with a triple challenge: extending the service life of its existing fleet, building new EPRs, and developing small reactors. The mid to long-term must also not be neglected, which requires financial and human resources, expertise and determination, for the benefit of fourth-generation reactors, research reactors, nuclear fusion and R&D.

This is required for continuous improvement, a guarantee of nuclear safety.

The new inter-ministerial delegation for nuclear new build (DINN) is gathering momentum, and its action in the coordination of administrative licensing procedures and public consultation processes is appreciated.

The French Act of 22 June 2023 on the fast tracking of procedures is designed to speed up the construction of EPR2 reactors. The legislation updates the energy plan: it has removed both the clause on reducing nuclear power to 50% of the energy mix by 2035, and the cap of 63.2 GWe on nuclear generation. The multi-year energy production plan (PPE) will subsequently be modified. The procedures have been simplified and additional provisions on nuclear safety and security complement the legislation.

More versatile organisations, better-proportioned means and realistic scenarios

The parliamentary commission of inquiry tasked with identifying the reasons for the loss of energy sovereignty and independence in France published its report in late March, which provides a wealth of information. This document illustrates how fewer than thirty years were sufficient to sabotage a long-term energy policy and to erode sovereignty.

It makes thirty proposals, including one which, in acknowledging the professionalism and high standard of French expertise, suggests “accelerating the hiring of nuclear safety staff and optimising the administrative organisation […] to be able to manage with the new workload resulting from the nuclear renaissance” and “to optimise the processes and management of resources”.

The July report of the Parliamentary Office for Scientific & Technological Assessment (OPESCT) on the consequences of the potential reorganisation of the French nuclear safety authority (ASN) and the institute for radiological protection and nuclear safety (IRSN), recommends consolidating and “gathering the human and financial means currently allocated to inspection, expertise and research on nuclear safety and radiation protection so they belong to a single and independent organisation in the future”. A draft bill, subject to consultation, incorporates these proposals, which were endorsed in principle by the French President at the Nuclear Policy Council (NPC) meeting. The ‘assessment, recommendation, decision-making’ sequence will continue to be respected and will remain understandable to both experienced observers and the public. The current Commission for decision-making at the ASN is already working independently of the assessment and expertise departments.

In April, the French Nuclear Energy Industry Group (GIFEN) presented the Match programme, a tool for matching capacity and needs. The nuclear revival is both a quantitative and a qualitative challenge in terms of competences. Twenty industrial segments (engineering, civil works, boiler-making, welding, etc.) represent about 80 trades and 220,000 jobs. The recruitment demand is about 100,000 new recruits over 10 years.

France and the UK face the same challenges: restoring the prestige of an industry that has long been left out of scientific and technical educational programmes and attracting more women into careers and professions in the nuclear sector. Competition will be fierce with other sectors affected by the government’s reindustrialisation policy, and the industry will need to demonstrate its attractiveness and ability to build loyalty in the men and women who will join it.

Finally, in its 2023-2035 generation prediction report updated in September, the French transmission system operator (RTE) sheds light on the challenges of the transition to a low-carbon society and examines three possible scenarios. The first scenario aims at achieving the decarbonising objectives between 2030 and 2035 through greater electrification and a marked increase in consumption (between 580 and 640 TWh/year in 2035 compared with 460 TWh in 2022, i.e. +33%

on average). Four levers have been identified, “none of which can be abandoned”: two through savings generated by energy sobriety or efficiency; two others through greater production by improving the availability of nuclear power and accelerating the use of renewable energies. The system will need ‘flexibilities’ by developing demand modulation and batteries as a priority (see Chapter 9).

Operator, regulatory authority: each with their own responsibilities

I have the opportunity here to point out what is obvious to experienced readers of IGSNR reports, i.e., the prime responsibility for nuclear safety falls on the operator. It must remain a force for innovation, making the most of its very high-level, well-dimensioned and dedicated R&D and engineering resources. Design engineering would, however, benefit from focusing on the needs and realities of operations from the very early stages to make things simpler and safer. This is one of the expectations of the current reorganisation of the EDF Group.

The independence of the regulatory authority is asserted through exchanges that allow each party to discharge its responsibilities. The assessment and decision-making processes for safety cases must be transparent, provided that the sequence of challenging technical opinions and releasing information to the public is in the right order so that the debate between experts retains the serenity, rationality and freedom that could be limited or hindered by too early a communication.

Nuclear safety and security of electricity supply should not be pitted against each other. A fair division of roles between safety stakeholders is essential at every level of each of our organisations. I see a dual risk in the current relations between sites and engineering with the ASN and IRSN: either the Operator holds back on what it has to say about nuclear safety and waits for instructions from the safety authority, or it goes in the opposite direction, and forgets to protect the operability of its facilities. In being too worried about an administrative view of nuclear safety, the Operator risks losing touch with the in-field reality. With finite human and financial resources, such an expenditure of energy and resources may lead to neglecting the maintenance of industrial assets.

The system will gain in mutual trust when the safety authority responds to a well-argued expert appraisal by the operator with a decision backed by a balance of safety gains and possible risks in terms of human and organisational factors, not to mention the financial cost compared to the safety gain (see Chapter 5).

The regulatory inspection and expertise system is now moving into a new era. It should, more than ever, promote technical dialogue between the Regulator and the Operator, in order to reasonably reconcile nuclear safety and the new industrial challenges in a transparent manner.

Make complex systems easier to operate

To improve nuclear safety, engineering has developed systems that justifiably require technologies that are increasingly more sophisticated and complex. The example of the aeronautics industry should inspire the nuclear industry. The sophisticated electronics in a fighter plane with fly-by-wire controls, aerodynamically unstable by nature, simplifies flying by providing improved manoeuvrability and safety. This design complexity frees-up the pilot, who can concentrate more on weapons systems. Safety and performance have benefited from simplifications resulting from the industrial prowess of complex systems.

Our reactors are ‘neutronically’ stable by design, but I am concerned that innovations and modifications aimed to improve nuclear safety are tending to make them more complex to operate. The ten-yearly outage programmes are more and more overloaded, and modifications can no longer be completed within a reasonable time frame during outage, nor assimilated by the operators. This gives rise to a heavy workload that has to be managed while the reactor is operating; the work is split over several operating cycles, which puts the plant in a state of being a permanent worksite, and is a factor of instability and source of fatigue for the teams.

I am not sure that operational safety is the clear winner here. The worst would be to convey an image of nuclear safety based solely on the assurance provided by the complexity of the modifications and investments made. The quote taken from Marcel Boiteux’s autobiography called “Haute Tension” summarises this risk very well: “better to have an imperfect system that keeps its inventors busy, rather than a perfect system that only requires obedience.” Trivialising risks can demotivate field operators if they see their role being devalued. Leadership and exemplary behaviour, individual commitment and involvement, collective responsibility, assessing situations: these are all key factors that must complement nuclear safety and reliability of the design (see Chapter 2). The safety authority can be a stimulus when needed.

Dealing with an increasing number of safety cases and the new-build projects will justify the allocation of additional resources to the safety authority. Only ‘strictly necessary’ new demands shall be imposed on Operators, who are already submerged by a profusion of questions.

Our Group must better standardise equipment and track plant configuration. The goal is to achieve an efficient supply chain and a uniform organisation between reactors of the same series, even on the same site. Following the example of the British new nuclear policy, the gains from replicating reactors, at least for the first six EPR2 units, will be the first illustration of this.

Lastly, the question of regulating the price of electricity, where Marcel Boiteux said, “clocks are made to tell the time, and tariffs are to tell the costs”, is decisive for the future of our Group. Giving EDF back its margin is a good way of preserving what already exists, investing in the near future and renewing the fleet, while guaranteeing the means for exemplary nuclear safety. The system chosen must be virtuous and sufficiently incentivising so that the Group, subject to performance obligations, can implement its vast industrial programme.

NUCLEAR SAFETY: A CORPORATE CULTURE THAT DRIVES PERFORMANCE

The Group is committed to a new reorganisation and a programme of operational excellence with the objective of strengthening its financial position, particularly by increasing its production. Four workstreams require everyone’s involvement: spanner time, digitalisation, competencies and operational performance.

Our company, even if not all its activities are nuclear related, would benefit from immersing itself in the nuclear safety culture. After ensuring that the design, equipment and procedures are equal to the risks and requirements, experience has shown that it is above all through the organisation and management of the workforce that performance is, or is not created. It always comes back to the operator or the engineer to perform whilst being conscious of the risks and managing them. The nuclear safety culture establishes the expected standard and the Operator’s responsibility-based competences. Finally, while it is based on established rules and defined structures, it only takes shape if it is supported by the motivation and involvement of all those involved. Having pride in providing a service to the public is one of the main drivers of performance.

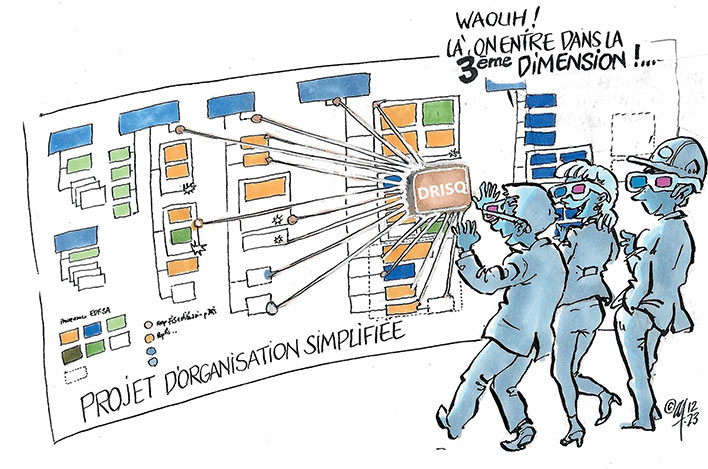

* “Wow, now we’re entering the 3rd dimension! …”

** Simplified organisation proposal.

Nuclear safety culture, the first line of defence

As Seneca wrote: “It is not because things are difficult that we do not dare, it is because we do not dare that they are difficult.” By prioritising skills over process, by teaching and training to ‘get it right the first time’, and by benefiting from digital tools without becoming a slave, trust is created, the desire to advance is born, and performance follows.

This calls for management commitment, for acceptance of its demanding yet considerate authority (in this order), for the skills of each person gained from rigorous training and accumulated experience, and for individual and collective accountability.

A nuclear safety culture is a state of mind that provides moral strength and encourages initiative and decision-making that goes beyond simply following instructions. This is our best line of defence in depth. It forces us to use our intelligence, to be rigorous in our preparation and implementation of actions, and to remain humble by knowing how to question or challenge ourselves. It encourages us to share good practices and pass on know-how through mentoring or learning.

If our organisations are complex, it is because we prefer to build barriers instead of bridges. Our company must simplify its procedures and hierarchal systems, it must share information along the lines of ‘everything except…’ rather than ‘nothing but…’; time could be saved, and efficiency improved for everyone.

To improve nuclear safety, engineering must ensure that what is complex to design is not complicated to operate. Modifying systems for the operator must benefit from its vast capacity for innovation.

Comparing yourself in order to improve

Sharing experience, job mobility between design engineering and operations, open discussions with the safety authority or the industry are, through improved mutual understanding, effective remedies to natural complexification.

The international review of stress corrosion cracking (SCC) in October 2022 and the recent international seminar on beyond 60-year operation, which brought together more than 250 people including 70 foreign experts, are good examples of the principle that ‘you can never be right on your own’.

Face-to-face exchanges between the designers, operators and inspectors can generate a wealth of information and remove prejudices. A technical visit, such as an in-field observation of behaviour, is a complementary yet essential method of assessing the relevance of a modification or the level of safety of an organisation, more than just an engineering drawing or analysis of a series of indicators (see Chapter 3).

These observations are widely shared by all nuclear Operators. I encourage the British and French to continue cooperating and encourage peer exchanges, particularly through WANO. Exchanges about leadership between the DPN and Nuclear Operations, the widespread use of joint peer reviews between the Nuclear Inspectorate (IN) and WANO, using the implementation of recommendations from corporate peer reviews: these are opportunities to benefit from the experience of others and to challenge oneself by looking through a different lens with humility and realism.

High standards and rigour: an effective combination

It would be better to pick two or three priorities to incite commitment and ownership, with fewer plans that are more focused on leadership and improving behaviours, the effectiveness of which is measured over short timeframes. Prioritised actions and quick definitive wins are better than taking a broad approach over the long-term.

Zero risk does not exist. Managing risk requires scientific and technical expertise from industry professionals. Everyone must benefit from a quality initial training programme, followed by regular and demanding continuous training with robust and honest debriefs (see Chapter 8).

Leadership relies on the powerful combination of standards and rigour. High standards are achieved by constantly stimulating our intelligence to reach the required levels of competence, while rigour guarantees accuracy and discipline in the accomplishment of our tasks, with or without procedures.

Making equipment more reliable, facilitating maintenance, perfecting how workers interact with the plant and operating documentation, reduces workload and frees up time. Reflection and preparation, guarantees of serenity, are encouraged in order to improve nuclear safety.

Recovering fleet performance is a daily task, which is done as a team and with our partners. The key condition is the fair distribution of roles for each player, who are aware of their responsibility, confident in their skills, and proud of their performance.

We must dream of our future success together to overcome the many challenges that lay ahead. The results of this year give us reason to be optimistic on either side of this small channel of sea that connects France with the UK.